The XY Model and Vortex Unbinding

In our previous explorations of statistical mechanics, we looked at systems with discrete symmetries: the Ising Model (up/down spins) and the Potts Model (

But what happens if we remove the discrete constraint? What if spins can point in any direction in a plane?

This brings us to the XY Model, a system that introduces continuous symmetry and forces us to confront a profoundly different kind of ordering mechanism based on topology.

The Move to Continuous Symmetry

In the XY model, spins are no longer simple integers. They are 2D unit vectors constrained to rotate in a plane. The state of site

The ferromagnetic interaction energy tries to minimize the angle between neighbors:

This introduction of continuous

According to standard theory, the 2D XY model should never order. Yet, simulations clearly show a phase transition.

Enter Topology: Vortices

The resolution to this paradox lies in topological defects. While spins cannot align perfectly over long distances, the system can develop “knots” in the spin field that cannot be smoothed out smoothly.

These defects are called vortices.

A vortex is a point around which the spin vectors rotate by exactly

- If they rotate counter-clockwise, it’s a +1 Vortex.

- If they rotate clockwise, it’s a -1 Antivortex.

The phase transition in the XY model is not a competition between ordered spins and random flips. It is a competition between bound vortex pairs and a free vortex plasma.

The Kosterlitz-Thouless (KT) Transition

This unique transition mechanism earned Kosterlitz, Thouless, and Haldane the 2016 Nobel Prize in Physics.

- Low Temperature (Quasi-Ordered Phase): It costs a lot of energy to create a lone vortex. However, it is energetically cheap to create a tight vortex-antivortex pair. Viewed from a distance, the +1 and -1 charges cancel out, leaving the background spin field relatively smooth (exhibiting “quasi-long-range order”).

- High Temperature (Disordered Phase): As temperature increases, entropy dominates. The thermal energy becomes sufficient to rip these pairs apart. The vortices “unbind” and move freely through the lattice like a plasma, scattering spin correlations and destroying order completely.

Simulation Results

We simulated the XY model using Metropolis dynamics and explicitly tracked topological defects by calculating the winding number around every plaquette on the lattice.

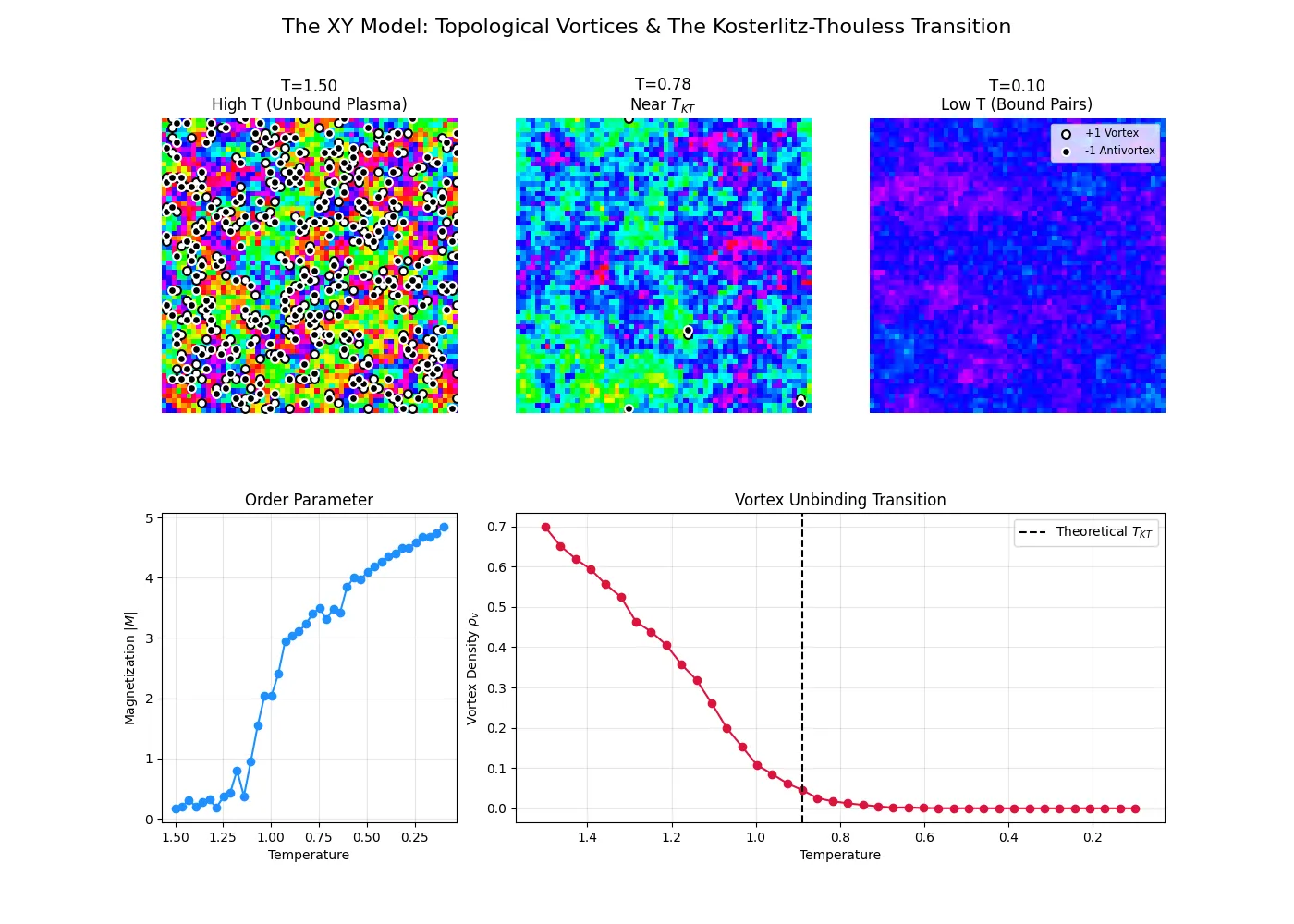

Visualizing the Fields (Top Row)

The snapshots in the top row perfectly illustrate the unbinding mechanism:

- High T (Left): The system is a disordered plasma. The background colors (angles) are random noise. Crucially, the image is covered in scattered white and black dots—these are free, unbound vortices roaming the lattice.

- Near

(Middle): We are near the critical point. The number of free vortices has dropped significantly, and we begin to see larger patches of smoothly changing color. - Low T (Right): The topological “cleanup” is complete. The lattice is almost entirely free of dots. Any defects that exist are locked in tight, neutral pairs (too small to see easily at this scale). The background shows smooth, wave-like gradients, characteristic of the quasi-ordered phase dominated by spin waves rather than defects.

The Quantitative Signal (Bottom Row)

- Vortex Density (Bottom Right): This plot is the signature of the KT transition. At low temperatures, the density of free vortices is effectively zero. As

crosses the critical threshold (dashed line), the density does not jump discontinuously; instead, it rises exponentially as thermal energy rapidly unbinds the pairs. - Magnetization (Bottom Left): While true infinite-range order is forbidden, in a finite simulation box, the correlation length can exceed the system size. The rise in magnetization here indicates the onset of quasi-long-range order where spin waves become the dominant fluctuation mode.

Conclusion

The XY model demonstrates that phase transitions can be driven by more than just local symmetry breaking. By moving to continuous spins, we uncovered a transition driven by global topological topology—the unbinding of vortex defects. This concept has since become fundamental in understanding phenomena ranging from superfluid helium to exotic states of quantum matter.